The car from Tijuana hummed beneath Macario Castellanos’s feet as it neared the northern border. In his bag beside him, some extra clothes were packed away and a few pesos and coins rattled. He was leaving everything behind him for a chance at a better future.

Hundreds of miles away, back in Guadalajara, Martha Alvarez, 17, held her ticket to Chicago tightly in her hand. She looked past the attendant and saw the plane that would take her brother and herself to a place they have never been. Although legal documents made her path easier, both Martha’s and Macario’s journeys to the U.S. were filled with hopes and dreams.

Macario was born in 1949 in Pocitlán, Jalisco, just outside of Guadalajara, to his parents José Maria Castellanos and Crispina Flores. He was one of 12 kids in the household, sharing with eight brothers and three sisters, and grew up surrounded by fields of crops.

At the time, his father was wealthier than most. José owned a ranch with over 200 goats, many cows, and two houses, and a small bussing company. Macario attended grammar school and graduated at the age of 14, then began working on his father’s land.

Eventually, Macario’s father made the decision to leave his inheritance to just one son. Though it may sound harsh, it was commonplace for the region. Few of Macario’s siblings had survived past childhood, and he was only one of two that received any education. Leaving an inheritance to a single child seemed like the best way at least one of them could succeed. Unfortunately, Macario did not receive it, and he soon left with his mother to find work in the city of Guadalajara.

“At first it was difficult because when I went to the city, I wasn’t even 18 years old. We didn’t know anybody and we didn’t have any money,” said Macario.

After some time, he was able to obtain a job at a local shop, though the pay was low.

Martha, born in Guanajuato, Mexico, was one of 10 children, with six sisters and three brothers. She was the daughter of Juaquin Alvarez and Alvenia De Guzman. Martha completed grammar school and high school, and was given the opportunity to work at a local bank as a clerk, however, she would leave it behind for the U.S.

In 1973, Macario crossed the U.S. border in search of work and more opportunities. He traveled from Guadalajara to Tijuana, and from there across the border to Los Angeles, California. He paid a ‘coyote’ to help travel across the border into the United States. From there his niece helped him take a flight to Chicago.

“The hardest part about crossing was the fear. It was scary because I didn’t know anybody there and had to travel alone,” said Macario. “There are a lot of poor people from many countries, Latin America, Central America, South America, that come here to work. Over there they pay, but not like [the U.S]. If you live [in the U.S] and you go to school and you get a somewhat good job, and you work, and work, and work, you can move up little by little.”

Martha immigrated legally in 1970, at the age of 17 through her father’s job, which provided her and the rest of the family with green cards and residential permits.

“He used to go to California to work, every six months… He picked a lot of apples, pears, and fixed our papers for us and the family,” said Martha.

Martha chose to immigrate to the U.S. and Chicago to support her sister who was pregnant and feeling lonely. Soon after arriving, Martha and her siblings began to take English classes at a local school, and found a job at Rush Hospital in the laundry unit.

“The reason we came to Chicago was because my sister was feeling lonesome, she was carrying a baby, and she needed the help,” said Martha.

After only a few months, Martha and her brother’s legal status was temporarily revoked during a routine immigration check after visiting Mexico.

“The immigration department asked us how long we stayed there, and I got confused. I thought he said how long we stayed in Chicago. So I said more than a year,” said Martha.

At the time, to maintain legal residency one could not leave the U.S. for more than six months.

“He thought we said more than a year in Mexico, and so he took my green card and my brother’s green card,” said Martha.

They were then deported back to Mexico, until her father was able to renew their residency papers at the consulate office in Mexico.

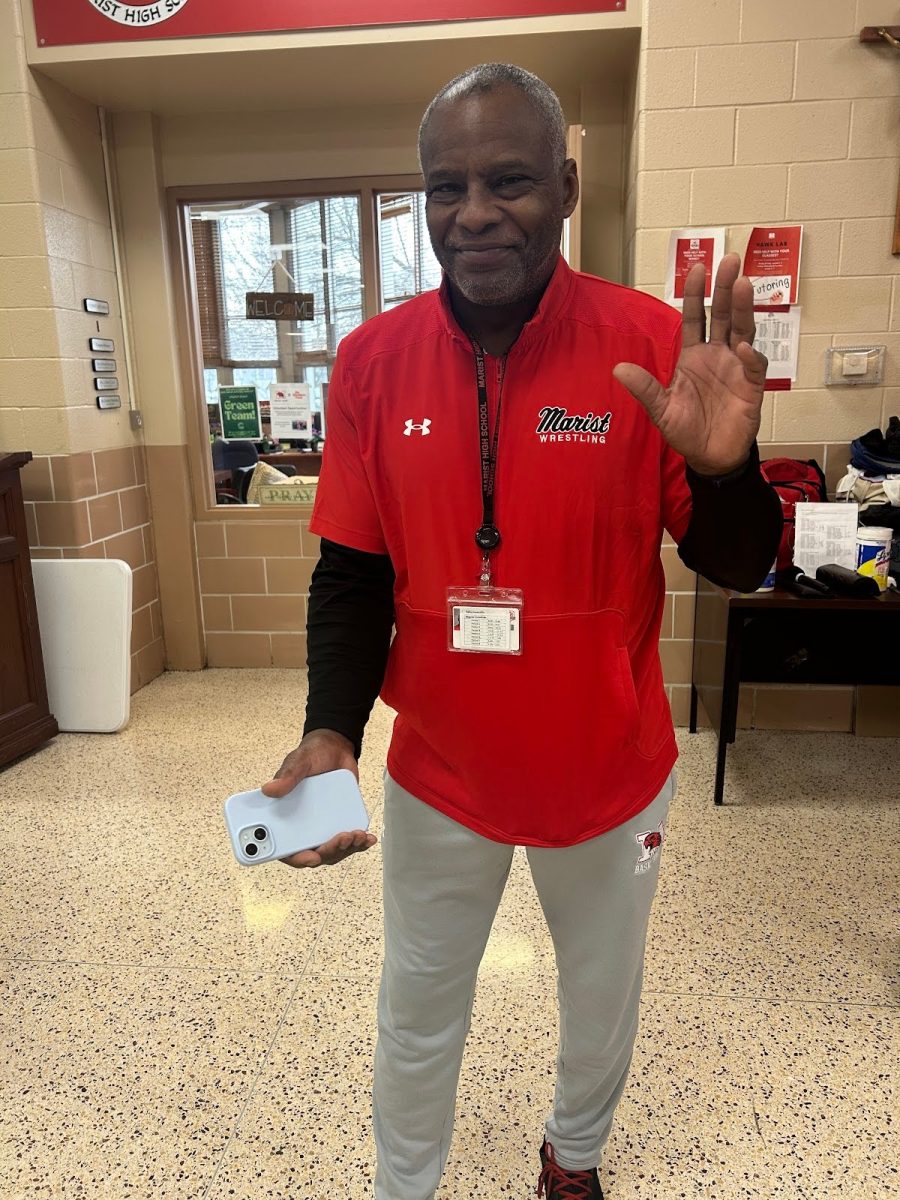

Macario’s first job was a busser in a restaurant. He was later helped by a friend to obtain a job at a local factory which paid slightly more.

“At that time there was a lot of work over here in Chicago in manufacturing and construction,” said Macario.

In 1979, Macario met Martha, and they began the lengthy process of obtaining legal status for Macario. The process involved traveling north to Canada first to obtain legal entry into the United States. Then traveling back to file paperwork at the local government agency in Chicago to apply for legal residency. In July of 1996, Macario fully naturalized and became a U.S. citizen.

After a few months, Martha’s boss insisted that she could get a better job working at a different hospital. She was sent to the uniform unit, where she dealt with cleaning, assigning, and delivering uniforms for all the doctors, nurses, and staff. After about 10 years, the hospital engaged in lay-offs which affected Martha despite her decade of experience. At the time she was carrying her first daughter, Jennifer Castellanos.

The hospital promised her a job after she had the baby, and she returned to the hospital within the housekeeping division. However, due to conflicts with her new boss, she considered quitting.

“One of the administrators talked to me because someone told them that I was going to quit. They said ‘Martha, don’t quit, all the nurses talked good about you. They’re planning on opening a new department, so you can go work there,’” said Martha.

She then became a junior assistant, helping to stock each patient room, and helping with patients’ needs. A few years later, the hospital asked her to go and apply for a different role that required further training and English speaking skills.

“I was afraid because my English was still [not good], but the nurses pushed me and said ‘you can do it’,” said Martha.

Balancing the new training with motherhood was a great challenge. Her other daughter, Sandra, had just finished grammar school and helped with housekeeping so Martha could study. She eventually passed all of her exams and became a full nurse assistant. She worked at that position for over 45 years before retiring in 2009.

“I was there for a long time and used to love to work with the patients,” said Martha.

Both Martha’s and Macario’s decades-long journey has shaped how they view current immigration policies.

“I feel bad because [people] suffer a lot even though I did not suffer that much, and I’ve seen children crying, families separated, and some people have been living here for a long time and what are they going to do because they don’t have papers,” said Martha. “Some of [the people they are deporting] are bad, but not everybody. They should [deport] the ones that are bad, but the ones that are good, why do they send them [away]?”

Despite the challenges for new immigrants, they have infinite gratitude.

“I miss the place a lot and you’re attached to the people over there because it was a small community, but I never regretted coming,” she said.